Who runs the Atchafalaya Basin?

One of the common questions that i get when i tell people that i work with the Friends of the Atchafalaya is “Who runs the Atchafalaya Basin, anyway?”, as if there is a single person with a magic wand and a trunk full of dollars, making decisions about which areas to mess up and which ones to “save.”

The answer, of course, is incredibly complex, but i’ll try to tackle part of it here.

Breaking down the question…

The first part of the question should probably be “What is the Atchafalaya Basin?

Once you decide which part you are talking about, the next question is “Who owns the land?”

And finally, in the specific instance of the Atchafalaya Basin Floodway System, the area inside the east and west protection levees, you can begin to list the different directives, responsibilities and agencies and the relationships among them.

After that discussion comes the non-governmental organizations that own, work or represent users of the Basin public or private elements.

…and that is just defining the scope of the question.

What is the Atchafalaya Basin?

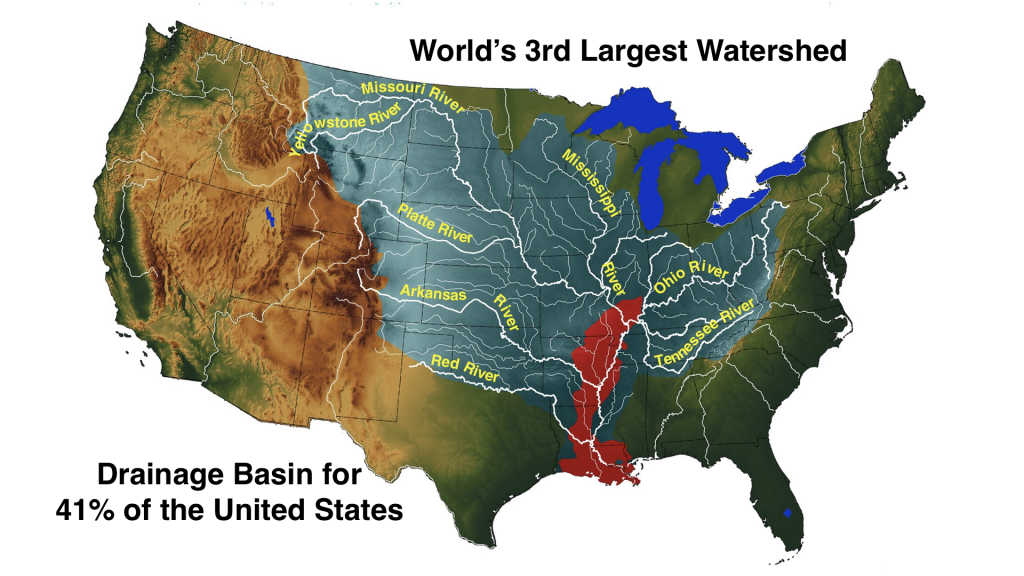

If we start with the “What?” part of the question, we can address the geology of the Mississippi alluvial plain, created by glacial scouring and then by deposition of sediment carried from far up the middle of North America over at least 6,000 years. The Atchafalaya Basin is a relatively young one and before it existed, the area was part of the sweep of the Mississippi River, with branches from the current Teche/Vermillion channels, all the way to Lake Pontchartrain. After the Mississippi chose the current channel, the Atchafalaya became a minor distributary of the Mississippi and not long after that, human intervention began to control the future of both rivers.

Nature created an annual cycle of river flooding and drainage of the land which resulted in varyng degrees of topsoil replenishment each yeae. Levee building along the Mississippi altered the natural cycle, while it allowed cities to thrive and agriculture to be more predictable, although we still didn’t control the weather. The opening and management of navigation channels allowed water to flow in different patterns and sometimes created alternatives that nature could choose over natural ones.

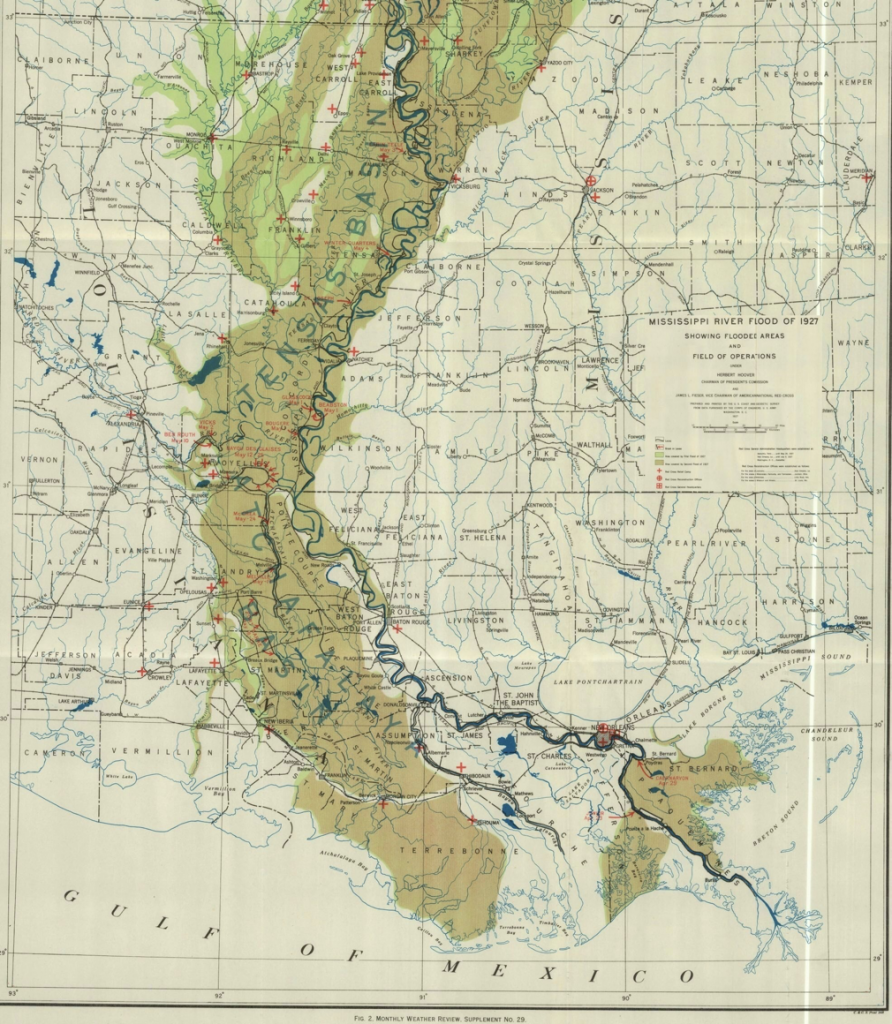

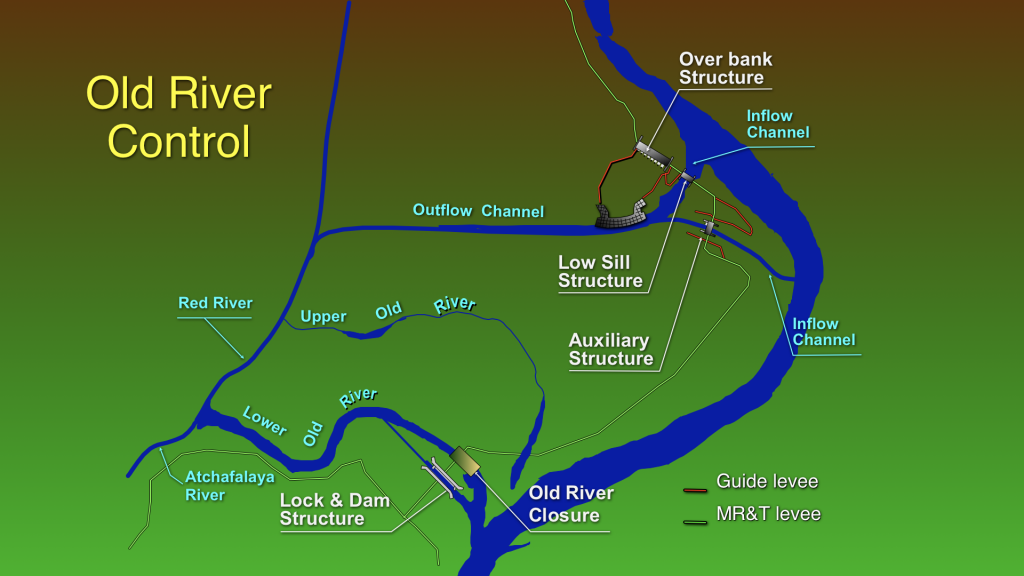

Such was the case with the Atchafalaya and Mississippi Rivers. Captain Henry Shreve and other believers in active river management cleared blockages along the Red and Atchafalaya Rivers and allowed water from the Mississippi a shorter route to the Gulf of Mexico than the one past Baton Rouge and New Orleans. Within a few decades, it became obvious that the new option for the Big River would require new and more massive control efforts to avoid the loss of navigation and the commerce that it supported, from the developed areas along the Mississippi River below the Atchafalaya branch. The Great Flood of 1927 brought home the significance of that potential loss. So were born the Old River Control Structures and the Atchafalaya Basin Floodway System, and, with them, the century-long battles over the funding, construction, control, and operation of the Floodways and the environment surrounding them.

the Mississippi/Louisiana extent

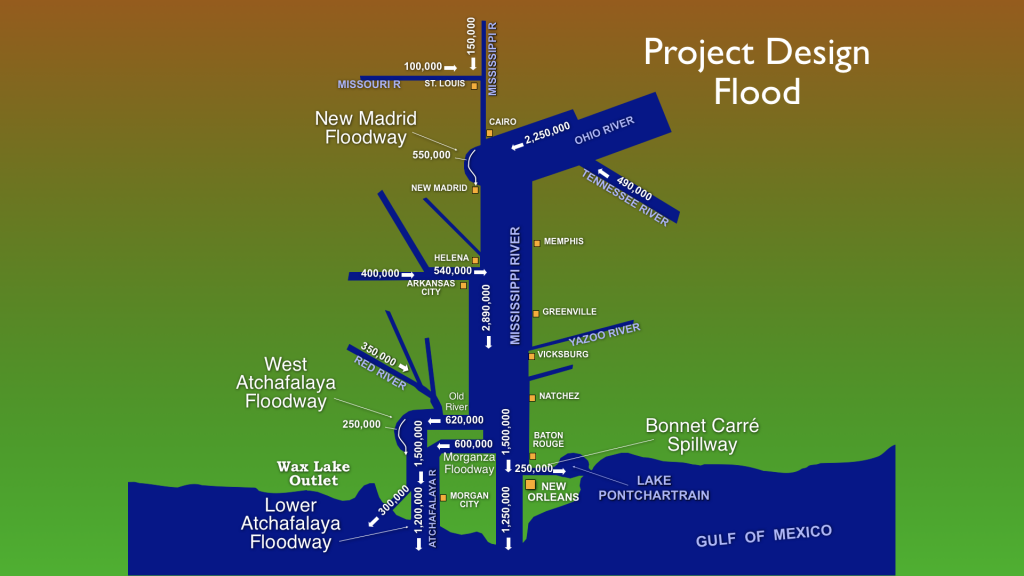

The flood protection system for the lower Mississippi River consists of impressive levees all along the river, plus several spillways or floodways in Louisiana that can divert up to half of the maximum flood flow away from the main channel. One is the Bonne Carre Spillway, just above New Orleans; it channels part of the lower River into Lake Pontchartrain, relieving the pressure on the New Orleans levees. The others are the Morganza and West Atchafalaya Spillways, which both feed into the lower Atchafalaya spillway. The Atchafalaya Basin Floodway System (ABFS) includes the three floodways but the area usually referred to as the “Atchafalaya Basin” when defining the floodways, is the lower Atchafalaya section, from US Highway 190 south to Morgan City and between the floodway protection levees. It has several primary inputs from the Old River Control Structures near Simmesport and a lesser used one near Morganza.

The Floodway has two primary outputs, through the Atchafalaya River at Morgan City and through the Wax Lake Outlet, to the west of the River. It also has a navigation connection to the Mississippi through a lock structure on the east side of the Basin at Bayou Sorrell. The lock provides a passage into a branch of the Gulf Intracoastal Waterway, which goes through another lock at Port Allen into the Mississippi.

max predicted flow down the Mississippi in the “Project Flood.”

But it is important to remember that the historic “Atchafalaya Basin” also includes land outside the Atchafalaya Protection levees, much of which is now developed and generally inhabited.

Who owns the land?

Most of the land outside of the levees is private, except, as in other areas of the State, for State Parks, local and state government buildings, and other specific areas designated for public use.

The total area in the Atchafalaya Basin Floodway System is about 800,000 acres. Inside the levees, about half of the land is public and the other half is privately owned. Flowage easements, or permissions to flood, have been purchased by the Federal Government on all private land in the Floodways. Environmental easements, which control additional aspects of land usage, development, and resource management, have been purchased on about half the land in the Lower Floodway and are authorized for purchase on all of it. Nearly 50,000 acres of land has been purchased from willing sellers over the past three decades, and about 25,000 more acres could be purchased, under current law.

Who are the players?

The US Army Corps of Engineers is charged with management of the Floodway System, but the Environmental Protection Agency, the US Fish and Wildlife Service, the Coast Guard, and the US Department of Agriculture Natural Resource Conservation Service (formerly known as the Soil Conservation Service) all have some responsibility in the Basin.

The Louisiana Department of Natural Resources, Department of Wildlife and Fisheries, Department of Environmental Quality, Department of Transportation and Development, Department of Agriculture and Forestry, Department of Health and Hospitals, Department of Culture, Recreation and Tourism, State Land Office, and Atchafalaya Levee Board, each have some jurisdiction over aspects of human behavior and management of public lands and waters in the Basin.

Other Federal and State agencies can get involved in the Basin under unusual circumstances; for example, the Federal Emergency Management Agency or other Homeland Security Agencies get involved in disaster relief and events involving security issues, as can the Federal Bureau of Investigation and the National Guard, but these agencies do not have regular responsibilities in the Basin.

The individual Parishes in the Basin provide law enforcement and participate with the Federal and State agencies in public works projects around and inside the Floodways.

Finally, there are towns and cities around the Basin which have an interest in Basin activities, even though most do not have incorporated areas inside the Floodways. Simmesport, Melville, Krotz Springs, and Butte La Rose are notable exceptions and are all protected in part by levees as the Basin rushes around them. Morgan City is just outside the protection levees but has a large investment in recreational facilities just outside the Floodway and a huge interest in the operation of the Control Structures because of its proximity to the Atchafalaya River and its minimum height above flood waters. Other communities around the Basin are also at the mercy of the flood control systems because their historic drainage underwent major alterations when the Floodways were created and the levees cut off natural flow.

So Who’s in charge of what?

The Corps of Engineers is directed by Congress to maintain an arbitrary ratio of water flow between the Mississippi. Red, and Atchafalaya Rivers at Old River. The plan calls for the total flow below the structure to consist of 70% down the Mississippi and 30% down the Atchafalaya, unless special arrangements are made to protect developed areas and/or levee structures below Old River. The Corps defines the design specification for the system as the “Project Flood”, in which half of the Mississippi Flow could be diverted through the Floodways to protect areas down-river.

So the day-to-day management of the control structures falls to the Corps of Engineers, as does major levee construction, channel maintenance, and major water management projects. Routine maintenance projects are handled for the State, by the Atchafalaya Levee Board and the Department of Natural Resources.

The Corps also operates the Indian Bayou Recreation Area and takes part in the management of the Sherburne and Atchafalaya Wildlife Refuges and negotiates the Environmental Easements and Federal land purchases inside the Floodways.

The US Fish and Wildlife Service is the lead agency for management of wildlife on Federal Lands but the Department of Wildlife and Fisheries manages all wildlife and fishery activity in the State and has a large responsibility in the Floodway. The State agency also enforces game and fishing license laws throughout the State, including the Basin.

The Department of Agriculture and Forestry provides forest management expertise and supports landowners and State agencies in the maintenance of healthy forests in the Basin.

The Office of State Lands manages State-owned land in and outside of the Floodways. The Office of State Parks, in the Department of Culture Recreation and Tourism (CRT) manages several State Parks adjacent to the Floodways. The CRT Office of Tourism operates the Atchafalaya Welcome Center at the Butte LaRose exit on US Interstate 10. The Welcome Center facility was built by the Department of Transportation & Development with Federal Highway funds and State funding through the ABP provided for exhibits.

The Atchafalaya Trace Commission manages the Atchafalaya National Heritage Area, under the Office of Cultural Development, also in CRT. Federal support of the Heritage Area is funded through the National Parks Service in the US Department of the Interior. The Parks Service also manages National Park properties outside of the Floodways but in the historic Basin.

The LA public has been confused by the similarity of the names of the Atchafalaya Basin Program and the Atchafalaya National Heritage Area (formerly the LA Atchafalaya Trace Heritage Area) since both were created in the late 1990s. This confusion was fed by the similar functions filled by the two agencies over the years. In the early years of the ABP, when the Heritage Area had limited funds, many of the projects that would now be funded by the Heritage Area, were initiated by the ABP. Now the ABP is limited to restoration efforts and the Heritage Area supports activities recognizing the cultural and heritage of the region.

The Environmental Protection Agency enforces clean air and clean water regulations but delegates much of that responsibility to the State Department of Environmental Quality, which works with the Department of Natural Resources to control resource extraction activities (primarily oil and gas production and delivery) in the Basin. The Department of Health and Hospitals gets involved when human habitation requires disposal of wastes into the waterways, which includes the entire Floodway System at times.

The US Coast Guard is responsible for water safety and works with the local Parish Sheriff’s offices to deal with public safety activities on the water. The Department of Public Safety and the Department of Transportation are primarily responsible for the roads across and inside the Floodways but can get involved in transportation issues on water under certain conditions.

Who handles the restoration efforts?

This review makes it sound like there must be armies of government officials out managing the Basin. If that is the case, why do we hear about the Basin being in bad shape and needing restoration efforts?

Recognition of the value of the Atchafalaya Basin as a natural resource is just now being achieved. For 200 years, the Great Swamp was seen by many as an area that was not useful for human habitation, and so was only made valuable when its resources were extracted. The inherent value of the environment in its natural state as a human life-support system, recreational resource, hurricane buffer, bio-diversity reservoir, and sustainable food source was not fully appreciated until those features began to diminish in value. By the time that political forces were marshaled to address the damages, much of the value had been lost.

Today, there are many different approaches to “saving the Basin”, and depending on your point of view, some of the restoration work may seem pointless or even counter-productive, but after many nears of neglect and even outright sacrifice of environmental quality for commercial gain, a scientific approach to evaluating the conditions in the Basin and the options for restoration. is finally taking shape. An awareness is rising that compromises will have to be made by all parties in order to retain some of the value of the formerly natural area.

Historically, the Atchafalaya Basin was an active and dynamically changing natural feature in the Mississippi Valley. The changes that were made during the conversion to a tightly managed floodway, barricading natural sources and blocking natural drains, accelerated some processes and halted others. We cannot go back to past conditions without endangering many developments that were created under the assumptions that the Floodways would protect them; we cannot put the oil and gas back in the ground to reduce subsidence; we cannot put back the century-old cypress trees that we cut for housing and furniture; we do not have the resources to move all the sediment that the new river channels deposited in the once Grand Lake.

What we can do now is what we are just starting to do – manage some aspects of the dynamic system that we have altered. We will never be able to restore the Basin to its former state, but we can make more intelligent decisions about how to balance flood control, transportation, recreation and resource extraction with conservation, water management, habitat regeneration, and ecosystem support.

There are two major agencies visible in Basin restoration but all the government agencies are important, as well as private landowners, non-governmental groups, commercial users, and private citizens. The two lead restoration agencies are the US Army Corps of Engineers and the Louisiana Coastal Protection & Restoration Authority (CPRA) Atchafalaya Basin Program.

Because of its flood control and transportation responsibilities, the Corps is often caught in its own web of resistance to significant change and must be driven by public demand through the Congress.

The Atchafalaya Basin Program (ABP) has recently been redesigned to be more responsive to citizen input and more transparent to public review and so is the most accessible of the government agencies, although not the best funded. The LA Legislature created the ABP under the Department of Natural Resources in 1999 and eventually transferred it to the CPRA in 2018. The approval in 2010 of a constitutional amendment to retain more of the State resource severance taxes for use in the Basin may eventually provide more funding for State restoration efforts. That has not yet occurred because of the economic limits built into the Bill.

So, public participation will still be the most powerful driver in the restoration process. Your continued input and vigilance, as an individual and through your organizations, will be the best enforcement tool for conservation and/or restoration of the Atchafalaya Basin environment.

crc/30